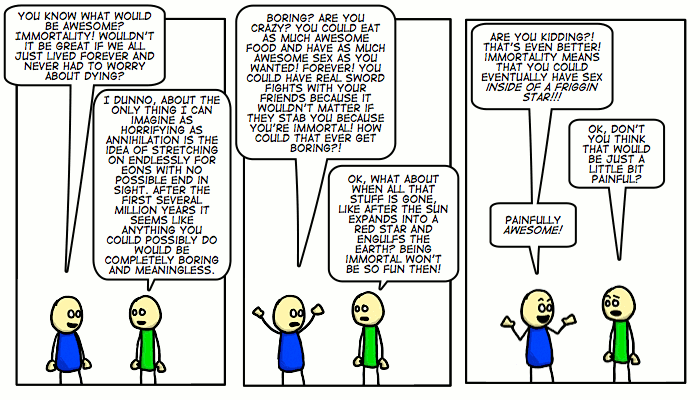

Ok so yeah, I’ve touched on the idea of immortality before (here and here). Hope you don’t mind another silly take on it.

Getting ready to head off to beautiful Gainseville in a bit for the FPA Conference. And yet here I am, taking the time to put together a quick comic for you. Do you see how much I love you? Do you?!?!

I feel the love, bro!

Break a leg! Does that apply here?

Emil: Excellent!

Cassie: Hah, I think it fits. Thanks!

Conditional immortality would still be awesome. As long as the condition was that you still wanted to be immortal.

I’d go with immortality and omnipotence (but not omniscience, that’s booooring). That way I could not only kill myself if I wanted to (omnipotence) but after everything ends I could make something new and have fun. And if I get bored for a bit I could always use my omnipotence to make myself kinda mortal and forget I’m omnipotent and immortal and go live with the crazy mortals. Maybe like a reincarnation thing. Until I wanted to remember that I am omnipotent and immortal again. Woo! Now that would be nice.

Hey, maybe I’m already like that but don’t know it because I made myself forget… Maybe YOU are all like that but made yourself forget! We won’t know ever! Because if you die it could be just because you are making it seem like you die (omnipotence) when you really aren’t! Omnipotence is the answer for all!

Canuovea

If you are immortal you cannot kill yourself. Omnipotence doesn’t change that. Immortality is forever. You cannot remove it even if you are omnipotent.

Isn’t logic nice? 😉

I misspelled my email address! Am I incompetent or what? (This would be the second or third time… second on this comic anyway). So I’m reposting this properly, sorry, don’t worry about the other one. That was really stupid. And thank goodness for the funny little picture things that remain the same! I wouldn’t have noticed otherwise…

Original message:

Omnipotence means that you can do absolutely anything, or at least that is the sense that I mean it in. All powerful, and power being the “ability to do” so able to do everything. But I suppose whichever you give precedence to.

Like that paradox that states “can god create a rock so heavy even he cannot lift it?” (it isn’t really a paradox). Yes God can create a rock that heavy, but after doing so God is no longer Omnipotent.

So… wait, if that is true, and God is omnipotent, could god completely destroy him/her/itself? Question for the theology I suppose… but a fun one. Can’t wait to being that up…

“Yes God can create a rock that heavy, but after doing so God is no longer Omnipotent.”

The question is merely a category error. There’s no number that could be used to measure the weight of a rock so heavy that God couldn’t move it. (Technically, it’s a category error even for any finite being — there’s no rock so heavy that we can’t move it *at all*.)

-Wm

For that matter, if Omnipotence means you can do anythings, are you still capable of failing without intending to?

@Everyzig

Maybe. But my guess would be not if you intend not to.

Canuovea,

Omnipotence is usually restricted to logically possible actions. Destroying an immortal being is not logically possible. Hence not even an omnipotent being can do it. Its the same with similar attributes such as omniscience (cannot learn anything), eternal omnipotence (cannot remove omnipotence) etc.

Yes, you are correct about the stone ‘paradox’. And yes it is not a paradox.

–

Wm Tanksley,

It is a category error? Are you sure that you know what that means? It seems not to be the case. Check:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Category_error

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Colorless_green_ideas_sleep_furiously

Emil, yes, I meant “category error”. Consider rephrasing the question: “Can God make a stone so GREEN that He can’t move it?” Neither the greenness nor the size of the stone have any bearing on whether the stone is movable.

“Can God make a stone so GREEN that He can’t move it?” is a category error but “Can God make a stone so large that He can’t move it?” is not. That it’s size (or weight) has no bearing is irrelevant. Did you read the links? It seems not. Let me explain then. A category error is when a sentence applies a predicate to a subject that cannot meaningfully have that predicate. Note the word “meaningfully”. Obviously it makes sense to apply “size” and “weight” to “stone”.

Emil, I read them — they seem to support what I said. You’re assuming that only the adjective-noun relationship can be a category error, but the noun-verb can also (ideas-sleep), as can verb-adverb (sleep-furiously). Wikipedia quotes Ryle as giving examples that don’t even fit the grammatical model you’re using at all, but rather a parts-whole confusion.

My example of replacing ‘big’ with ‘green’ is to make it clear that the fallacy is in assuming that bigness is in the same category as immobility. It’s not, no more than greenness is. (Well, to be fair, a big (massy) item should have more inertia, but that doesn’t mean it can’t be moved; it just means that it reacts with more force against an acceleration, but it still gets accelerated.

Ahem. I meant to close that last parenthesis.

Wait wait wait… killing an immortal is not a logically possible action? Fair enough, but to say omnipotence is limited to what is ‘possible’ doesn’t make sense to me. If there is anything that you cannot do you are NOT omnipotent. Anything at all. Or at least that is how I see it, and some would agree. Perhaps ‘possible’ is subjective though… I mean bringing a dead guy back seems pretty impossible… but apparently God did it. So it seems God could (theoretically) do the impossible! So… was it just a subjective impossible? I’m making no sense…

“You’re assuming that only the adjective-noun relationship can be a category error, but the noun-verb can also (ideas-sleep), as can verb-adverb (sleep-furiously).”

I am not. I never even heard of this.

“(Well, to be fair, a big (massy) item should have more inertia, but that doesn’t mean it can’t be moved; it just means that it reacts with more force against an acceleration, but it still gets accelerated.”

You are even accepting that it makes sense to apply size to stone. But you are saying that it has no effect. That may be true, but that’s irrelevant. It makes sense. Thus, no category error.

This seems to be a waste of time. Maybe you will get it this time. It is my last try.

“If there is anything that you cannot do you are NOT omnipotent.”

That’s reasonable, Canuovea, but only if you accept that the members of the set of “anything” are actual “things”, not non-things. Category errors aren’t things; they have no correspondence to reality.

You later mention “pretty impossible”. That’s a category error (specifically, applying “somewhat” to “impossible”). A deed is either impossible or possible; it can’t be somewhat impossible. Bringing a person back to life involves specific physical (and perhaps spiritual) manipulations; it’s logically (and maybe physically) possible. The word you’re looking for is that bringing a person back from the dead is unheard-of and of unknowable difficulty; not that it’s impossible (although you could say that we don’t know how to do it, but even then it’s not certainly impossible; we might succeed by accident).

-Wm

Emil:

I’m not saying that applying “size” to “stone” is a category error. Can you please do me a favor to help me communicate in the future, and show me what I said that made you assume that’s what I meant? By replacing the word “big” with “green” I intended to remove all possibility of a misreading of that sort, and I’m very puzzled that it didn’t work.

I’m saying that applying “large” to “immovable” is a category error. It makes no sense whatsoever to talk about anything being immovable simply because it’s big. This was the fundamental thing that Archimedes realized with his famous statement that with a lever big enough and a place to rest it on, he could move the world.

Once again, I’m not saying that

And by the way, “I never even heard of this” isn’t a logical defense against my claim that you’re limiting category errors to noun-adjective. It would be more convincing if you’d prove it by giving an example of a category error that isn’t noun-adjective. So far, I’m not persuaded, because not only have you not given anything but noun-adjective, you’ve actually attributed a belief I specifically contradicted to me in order to find a noun-adjective claim when I talk about category error (specifically, you said that I was talking about big-stone, when I specifically gave an example that involve green-stone and said it was the same category error).

-Wm

Lets take another approach and stop talking about rocks. Maybe then we can avoid this “category error.”

“Can God do (or create) something that makes it impossible for him to do something else?”

This is, of course, given that God is absolutely omnipotent (though adding absolutely does seem a bit silly to me).

The short answer is, for me, yes. Theoretically if God did do such an action, then after doing it God would no longer be omnipotent. So God is so powerful that he (or whatever!) can make himself (whatever) not omnipotent. Cool.

This could apply to the immortality idea. If God made itself so immortal that God could not completely destroy itself then God is no longer omnipotent. Likewise, from my perspective (in which God is not always logical, or doesn’t need to be… this is what I have taken away from many debates and conversations with staunch believers, which were generally nice conversations), if God is immortal and could not destroy itself completely then God is not omnipotent.

So… Premises:

God is omnipotent (can do anything imaginable and not imaginable as well!)

God is immortal (lives forever… cannot die?)

Reasoning:

God can destroy self… (is omnipotent)

God cannot die (immortal)

God cannot destroy self?

Contradiction, and anything follows from a contradiction so:

Conclusion: God likes pink bunny rabbits… They go well with mustard… And taste like bubblegum.

Seems like something is wrong with the premises? Either God’s omnipotence has limits, (and in my mind is therefore not omnipotent), God’s immortality has limits, or the logic doesn’t matter at all.

I think the predicates “taste like bubblegum” and “go well with mustard” are also contradictory.

“Can God do (or create) something that makes it impossible for him to do something else?”

Like what? The rock example doesn’t work, but surely there’s something. I’ve come up with three possibilities, and discarded them for being easily defeatable.

“This could apply to the immortality idea.”

Doesn’t work — God is immortal because God exists outside of time. We can’t even talk about killing or destroying something that isn’t subject to change.

Hey, I thought of one. God does allegedly seem to want (some) humans to live forever (after dying), so that argument DOES seem to work. Presumably that means that God couldn’t kill them without breaking His promise… Darn, that doesn’t work. The problem here isn’t that God CAN’T kill them; it’s that He doesn’t want to kill them.

I’m not coming up with any examples.

-Wm

Wm: Can God make a burrito so hot that even he cannot eat it?

Chaospet: since anything follows from a contradiction… you can logically deduce a contradiction!

Fun Fact: There was this one logician who proved he could lawfully set up a dictatorship in the US because he found a contradiction in the constitution… He did this during his application for citizenship. Forget who, could ask my Symbolic Logic Prof, but I think that he was one of Einstein’s buddies (NOT my symbolic logic prof, the other logician guy).

Wm Tanksley: First off, don’t bother trying to come up with examples about what that “something” is. Let’s just assume there is something that God could theoretically do (but our mortal minds cannot comprehend it) that would make God not able to do something else.

God is immortal because “God exists outside of time” was not a premise I was working with. But hey! Why not? Would God still be immortal if God made himself exist inside of time? Could God do that? Well, if you believe most of the Bible then it would seem possible. I highly doubt that God exists completely (including always) outside of time because of the theoretical influences on our own time line. Also if God “lives” in Heaven, and as time goes on the amount of souls in Heaven increases… God is most certainly a witness to time at the very least. Though seemingly not effected by time (being immortal)… But that was off topic slightly…

The way I see it is that being omnipotent means being able to do anything, anything at all, no matter how illogical, contradictory, and contrary to the laws of physics. Only then does a being of any kind have absolute power.

Being omnipotent is like a contradiction: it implies everything and anything if the omnipotent being wills it, no matter how illogical or contradictory. Someone omnipotent could make themselves omniscient, or not omniscient, immortal or not immortal, physical or not physical or both! An omnipotent being could make itself exist or not exist, or have always existed. An omnipotent being is not Logical (unless it wants to be) and does not obey the laws of logic (unless it wants to).

God is supposed to be omnipotent.

God (if it does in fact exist) therefore does not require logical or scientific proof to exist. God is not logical (unless it wants to be). And so we have no proof that can convince me either way as to it’s existence.

“Can God make a burrito so hot that even he cannot eat it?”

Good one. But no matter how hot, he’d just add a ton of mustard and bubblegum, and he could eat it again. Yum!

-Wm

Canuovea: I was trying to come up with any example to quell my suspicion that there’s no such thing.

God existing outside of time and inside of time aren’t mutually contradictory — I can exist outside and inside my house, for example (by standing in the door), or I can exist outside and inside of a novel (by writing myself into the plot). Even more, killing myself in the novel won’t kill me outside the novel.

I don’t think it’s useful to define omnipotent as “able to do anything, no matter how illogical”. The worst problem is that it’s not what’s meant by most theists when they use the term; any argument you construct against them is a strawman. A lesser problem is that the ones who DO mean that will just nod their head and say that Allah can fix that up too (Islam holds that Allah can create truth by saying it, regardless of logic or history).

-Wm

Are you sure that isn’t what most theists mean? If so then it appears that Allah gets the better of God (though they are Technically the same entity). It would seem, then, that the usual description of the Christian God is what could be considered limited omnipotence, and the Islamic God, Allah, has full omnipotence (since you pointed out the difference between the two versions of God, and “omnipotent,” in the first place).

And if being “able to do anything, no matter how illogical” is not omnipotence then what is it exactly? I cannot think of a different word. Are there degrees of omnipotence? Is “Allah” more omnipotent than the Christian “God” then?

And of course an omnipotent being could make me believe it is omnipotent, or that it exists, or it could even make me believe by willing someone else to convince me (using a banana perhaps). But that doesn’t mean that a simple individual human could convince me without logical and scientific proof. Saying a god (any which one!) is illogical, or doesn’t need logic, etc will not convince me of anything.

Yes. There are currently more Christians than Muslims, and this has been the understood meaning of the term in the respective theologies, so I’m sure. Whether this is what uninformed people think is irrelevant, I believe; I doubt most of them have even thought out what it means to say “anything” in “God can do anything”.

That would be significant if it were possible for them to compete in that manner. If it were, one could also say that because God cannot change, God is more capable of persistence than Allah, and is thus superior. But this is irrelevant; the two cannot exist separately at the same time.

What does “Technically” mean? It’s not philosophically possible for the Christian God and Allah to be the same being — Allah is totally non-immanent, while God is immanent; Allah is one in person and being while God is three in person and one in being; Allah associates with no one but Himself, while God associates with the Son and the Spirit (the latter is phrased according to the Islamic convention; Christians would phrase it differently).

It happens to be Islamic doctrine that the two are the same, but they can do that only by also claiming that all the distinctively Christian doctrines are false. Saying that makes them “technically” the same seems to beg the question in the favor of the Islamic side. (Some Christian sects have attempted to turn the rhetorical trick around, claiming that Allah is God but Moslems are wrong about His attributes; I give that the same response.)

I’ve never heard this “usual description”, but I have no objection to it, given that people only use it in a context where everyone understands the special meaning of the word “full”. I think it would be wiser to use an obviously technical term like “omnipotence of will” versus “omnipotence of action”, or even “omnivolence” versus “omnipotence”. God can do anything that He could possibly want, while Allah can do anything, whether it’s possible to want it or not.

I don’t have a problem with taking it either way, but I do see a need for a distinction, however it’s phrased. English has a number of distinctions for possibility, after all: probable, possible, counterfactually possible, physically possible, logically possible, possible to imagine… These aren’t all just levels of possibility, they’re often different types of possibility.

Only, of course, if it actually existed :-).

I’ve seen one guy use a dollar bill, but not a banana.

I agree, although I would say historical proof is important and scientific proof is almost irrelevant — the only relevancy would be that science depends on a consistent logic, which suggests that if a god is responsible for the universe, that god has to be interested in some level of consistency. I’m not saying this to rule out Allah, but that suggests that if He exists, He has to display some consistency in order for the evidence we’ve historically collected from science to be consistent with His existence.

I don’t think it is; I think it’s intended to fit the data presented in revelation, rather than to convince anyone. For that matter, this is the same reason the Christian God is presented as being a trinity; it’s not something that’s explicitly claimed in divine revelation, but it’s the only way to make any sense out certain aspects of the revelation.

I don’t see any reason why someone would be converted specifically by the claim that Allah can do anything volitionally, or that God is both three and one in different senses; but if one is otherwise impressed by the alleged revelation for other reasons, those details might remove an obstacle to understanding the full impact of the revelation.

-Wm

Whoah — I accidentally used “blockquote” tags, and it actually looks decent! I didn’t know I could do that here. Nice. If anyone wants the same effect, just ask and I’ll explain how to do it.

Whew!

I should have said are you sure that is what most Christian theists mean. The idea that all Christians would believe that description is misleading (as are most blanket statements). I have talked to one who saw things along the lines I laid out. So there is room for interpretation.

“God is more persistent than Allah…” and is thus superior. Well, I suppose that it depends what you mean by superior. God is limited while Allah is not, and it is unlikely that either of them would will to destroy themselves in either case. And saying that God could do anything that He would possibly want is also a little problematic. What if God “wanted” to mess with the time line or logic or whatever? How do we know what God “wants” to do? We don’t know that God doesn’t want to commit suicide but can’t (as unlikely as that may seem). Muslims would know that (given the previous description of Allah) with a greater degree of certainty because obviously if Allah wanted to destroy itself then He could. He just doesn’t.

“Technically” meant that they are, in theory, referring to the same entity (even if they do assign other attributes), that entity is (or was) the Jewish God… who just decided to change things up. And as for the difference of association… I thought that Father, Son, Holy Spirit were actually one God in three beings. Allah is one God. And so is the Jewish God (but this one has a tendency to split itself into 3 separate “angels” when going about it’s business). There would actually be little conflict (and if Allah is “fully omnipotent” as I call it, then it would be easy to appear as one while being three, or appear as three while being one, but this is getting a bit into the “haha anything goes” zone). The concept of three beings being one being (as opposed to the heretical idea of a hierarchy that was purged after the Niccean Creed), seems inherently illogical as two beings cannot occupy the same space at the same time. So the Christian God also defies logic by it’s definition (if that is the definition… I could be wrong, but I distinctly remember that).

My definition of omnipotence would probably cover all those different types of possible. But still…

Oh I have been assuming that God exists throughout. If I didn’t assume it than there would be no point eh? And believe it or not there is someone who claims to prove God’s existence with a banana. It’s really pathetic. Worth a laugh though.

History is an interesting thing here. History is a) written by the winners and b) not exactly the most accurate even when it seems to be. Over reliance on history is dangerous. There is plenty of “historical” evidence for both the “Islamic” and “Christian” Gods, but as you said, their apparent attributes are contradictory… so which History is right? And then there are the conspiracy theories: like: “Oh someone quickly switched out for Jesus while he was carrying the cross… so he didn’t actually die… So there goes the idea that Jesus came back from the dead…” Good luck either proving (or disproving) that with history!

And I am about to start Political Science class… so have no time to go over this… never good… Well. On to Nietzsche!

All of the major sects/denominations/etc have that definition of omnipotence, and it arose VERY early in church history, in fact inherited from the Jews. Anyone disagreeing with it is either willfully departing from Christian doctrine (presumably because they have reason to think it’s wrong; I’m not implying that they’re factually mistaken) and is thus not counted as a Christian opinion, or simply hasn’t thought about it and thus isn’t worth counting as an opinion.

No, it depends on what *you* mean — you’re the one who brought it up. 🙂 I don’t think it depends at all, since the concept is pointless. There’s no way to have the two duke it out, since they can’t possibly _both_ exist distinctly (even though hypothetically they’d both be the same person if the Moslems were right).

I’m being too harsh, though, because I’m jealous that you made this very good point first, and I should have noticed it.

Ooh, good point — but it wouldn’t work in this particular case, because the Islamic Allah’s revelation happened after the Christian God’s revelation, so the most recent revelation takes precedence. But in general, good point. Actually, this is what the Bahi’ists say; that all the revelations (of all religions) are important, and were actually correct when they were given, and have some value even now.

Interesting, if true. I’m pretty sure that most modern Jewry doesn’t accept that; it’s possible that some did before Christianity (I haven’t heard of it), but the dominance of Christianity made it impossible to keep without losing Jewish identity. The very primitive Judaism, of course, didn’t do that at all; they were nominally henotheists, so they didn’t bother with angels, just other lesser (or forbidden) gods.

Sorry to interrupt. Correction — three _persons_ in one being. NOT three beings in one being. That would indeed be a direct contradiction.

The Christian God occupies neither space nor time; he could be said to underlie it, but mainly He exists outside of it (ditto the Judaic YHWH). The Islamic God is a little less clear; but the most I could say is that He doesn’t underlie creation (because He’s not immanent). Mormonism is different; their God is two things: first, an impersonal principle of eternal progression, and second a Father God named Yaweh who lives on (or near) a planet named ‘Kolob’ and has much the same form as us, but glorified.

Anyhow, sorry. My point is that although the Christian God defies physics, He doesn’t defy logic. “No two bodies in the same place at the same time” is a principle of physics, not logic; and “a thing cannot be both three and one in the same way” doesn’t apply because the Christian God is one in being, but three in person (different ways).

Allegedly.

Oh, I agree. But that makes it less useful, not more, since no actual religions use that definition — even Islam says that Allah has some self-imposed requirements that He’ll stick to.

You are equally free to say the same about science, if you wanted to simply dismiss it — it’s equally true. I’m not here to argue historical evidences for any side; I have done so, but this is NOT the place. But philosophically speaking, we have to have some respect for history in order to reach ANY conclusions at all; otherwise it would be perfectly sensible to dismiss everything on the grounds that a malevolent deity MIGHT have created the entire universe 5 minutes ago. The question is how *much* respect to give to history, and how hard to work to reach a high enough level of confidence. But I’m certain the correct answer is not “no respect at all”, because if it were, we couldn’t trust our own memories (or notes) at all.

Enjoy Nietzsche! Poly sci was one of my favorites, because although my first prof in a poly sci class was just about my opposite politically, he was also a brilliant actor and teacher, and always put his full effort into every class. Very enjoyable, fun to debate, and fair. Hope your prof is as good.

-Wm

“The most recent revelation takes precedence.” Unless God meant to reveal slightly different things to different groups of people on purpose. That would mean that each revelation works to it’s own specific group. There could be any number of reasons for doing this…

Okay, three persons in one being (but we normally assume a person is a being. Hmm. My bad there).

Christian God occupies neither space nor time. Fair point. Physics wouldn’t matter.

Useful… well it if I die and meet God I can ask him and get this whole thing sorted out… and maybe get him to destroy himself too (Oh? You can? Prove it!). That would be… kind of awkward.

History is generally less certain than Science and Mathematics. But it is still useful of course.

More later perhaps, need to go to Literature class… (Canterbury Tales at the moment).

Canuovea, I agree with everything you say this time :-).

Oh, and when I mention the most recent revelation, I should have specified that this is Islamic and Bahi’ist doctrine, not a general philosophical premise :-). I can imagine a Universalist faith in which every revelation is ultimate, any are allowed to conflict, and only the BEST solution is correct (rather than the most recent). It would be kind of a cruel joke, since it wouldn’t be solvable by us time-bound beings, but it’s conceivable. But then, reality kind of IS a cruel joke :-).

Yes, history is less certain than mathematics, but NOT science. History is intrinsically part of science, because science requires observations that are reproducible. How do you know whether an observation is reproducible if you can’t trust history?

-Wm

Well, when I say science I mean natural sciences that use the scientific method. Social sciences like economics, political science, etc, are not as certain simply because they have humans as their subjects, we are generally more unpredictable than nature (for now anyway)… History isn’t quite a social science, but it still deals with humans and is definitely often contradictory. Take this for example: In the US the war of 1812 (against Canada and Britain) is often considered a draw (perhaps depending where you are). Everywhere else that matters it was considered a defeat for the US (Bankrupted and the White House was burned down, though neither side took land). Too early? Ancient historical records are just as questionable if not more so. There was one battle between the Hittites and Egyptians. Both sides wrote that they won. All our primary sources should be considered non-objective because every person has a kind of bias and point of view. History is not nearly as uniform as science is. And history isn’t as certain as science is, but it may very well be more certain than the social sciences.

This lack of total certainty is to be expected, and does not detract too much from the usefulness of history, but it needs to be acknowledged and taken with a grain of salt. If there was historical documentation of aliens nuking Atlantis I would be just a little bit suspicious. In science we can recreate experiments, we cannot (as of yet) travel back in time to observe actual historical events and have to rely on other sources that are questionable. That alone is a advantage that science has.

And how can you know if an observation is reproducible? Try it, over and over. That does kind of rely on accurate historical records of the experiment. However, why bother needing to try to reproduce something if you are just as certain with history as science? Surely there is no need because the historical record already tells you what the result is going to be! But it needs to be verified through science. But yes, historical (scientific) records do play a role in science, but it is only part of a whole, and the results of a science experiment done properly are more convincing than a 200 year old manuscript that tells you what that same experiment would do.

But I’m rambling now. Not good.

And yes reality can be a cruel joke… but “Always look on the bright side of life, hmm mm, hmm mm m m mm Always look on the light side of life…”

Oh and that Logician guy who found the contradiction in the US constitution was: Gurdel. Or however you spell that… Unless the historical records are incorrect!

Thought of a few things: About the idea of God splitting himself into three angels. I remember reading Genesis, particularly just before Sodom and Gomorrah went boom, and this translation claimed that the angels were God, or something like that. It wasn’t the King James bible but I could dig it out if necessary. Anyway three “angels” came to see Abraham, then two of them left to Sodom and one remained to haggle about what would mean that Sodom would be destroyed with Abraham. Anyway, it wouldn’t be far fetched for an omnipotent being to make itself three separate persons…

Also, can God destroy the immortal soul of someone he doesn’t like? That is an “immortal” soul after all… Hmm.

Anyway just extra stuff I though of.

Understood. And with this I have to admit an error.

I said that science depends on history. The genius of science is precisely that the scientist does NOT depend on history, except for the minor ability to credit the original discoveror or the original experimentor. That’s the extent of my error. What I should have said is that our reading of science — i.e. the answer to the question “what does science say about this?” is precisely, if not entirely, a historical question. The answer requires that one dig up documents showing that experiements were done, than peer reviewers agreed, that null hypotheses were duly formulated and discarded, that the experiments were reproduced at different labs, that disputes were largely settled, and that the old people who disagreed are now dead (sorry, got a little Kuhnsian there). We could shortcut all that by finding a “scientific consensus”, but the process of finding and verifying that is precisely a historical task.

The sciences that aren’t “natural sciences” are not as repeatable because they’re not embedded in a natural framework. “Nature” is precisely the way a thing will always work (see “Physis” in Wikipedia for some, ahem, history). Because they’re not repeatable they’re not as certain as the natural sciences. Yeah, adding humans makes things messy, but so long as the added humans keep things natural, it’s still natural science, and still as certain as natural science can make us.

BTW, it occurs to me to mention that one of the characteristics of good science is tentativeness. That’s the opposite of certainty.

Anything that humans deal with deals with humans, and is therefore “often contradictory”.

But this presumes that determining which single side won the war is the purpose of history. It would seem more useful to note that the history behind the war is actually reasonably clear, as are the consequences.

The sources of knowledge in history are of often indeterminate quality. So what? The same is true in the natural sciences. The real problem ancient history has that modern history doesn’t is that we can’t simply go collect more data (although it happens that we sometimes DO find data that we missed before, as when we found the Codex Sianaticus).

This tentativeness is the mark of all science, not only of history.

That’s not what’s relevant. The reason you retry isn’t because you think the historical record is wrong; it’s because you think the experimental interpretation (which you trust was correctly recorded) was wrong, and different measurements will confirm your interpretation.

I agree.

But an experiment that’s been known to produce consistent results for 200 years — and whose meaning was agreed on for all that time — is a very reliable bit of knowledge indeed. Knowing that scientists thought that so long ago is very, very interesting.

Literally, LOL. When I say literally, I mean literally, not metaphorically.

Grin.

-Wm

Genesis 18. What you read wasn’t a translation, but a paraphrase — it gave way more detail than is present in the known text. There were three men, Abraham fed them, they prophesied to him, then a single person identified as YHWH starts talking, and the three never are mentioned again. It’s a rather difficult text to interpret, but they weren’t called angels, the text doesn’t say whether one of them (or all of them) was YHWH, and doesn’t even say what happened to them.

Opinions differ, but it’s hard to claim man’s soul is immortal, because we DO die, which means the soul must experience death even if it, itself, doesn’t become extinguished by it. Hypothetically :-). Anyhow, “immortal” means “undying”, not “indestructible”.

-Wm

Wow.

“BTW, it occurs to me to mention that one of the characteristics of good science is tentativeness. That’s the opposite of certainty.”

Yes, of course, but that tentativeness has to be balanced with a degree of certainty. The point of science is that there is a basis (what is being claimed, premises, etc, say, the Earth orbits the Sun) that fit with actual observations. If these observations are all consistent in affirming these premises than we can be “fairly” certain. The tentativeness comes in by saying that if there are observations that are not explainable with the current premises then we need new ones. So there is a degree of certainty there (like in logic, given these premises it follows that… for Science: these observations support this…). Just putting this out there for safety sake.

Social sciences are not in a natural framework and so not as certain. Okay I agree, makes sense.

“Anything that humans deal with deals with humans, and is therefore “often contradictory”.” Hmm, only to a degree. In the natural sciences the problems are in the people performing the experiments, which is better than both the people performing the experiments AND the subjects.

” It would seem more useful to note that the history behind the war is actually reasonably clear, as are the consequences.” Okay, history is the recording and keeping of records, the interpretation of history is linked but different.

When there are people interpreting the history that suffers from the same error as the having a scientist interpreting the results of an experiment. Error and bias in the interpreter (especially if the interpretor is somehow sympathetic to some side or interpretation). Then there is a further flaw in the sources themselves. They are written by humans who also have bias and who can make errors. And remember, our Primary sources are not always from the observations of person who was directly part of the events, it could be a friend recording what happened, or someone who only heard about the event being recorded.

And then there is the deliberate manipulation of data by the recorder as well. “History is written by the winners…”and yes it is. There is the additional layer of uncertainty because what is being documented could very well be a lie.

In the Sciences we have to deal with the bias and error of the experimenter. Not what the results are because the results speak for themselves, and aren’t about to lie (unless the experimenter messed things up in setting it up). History has to worry about the truthfulness of whoever witnessed the event, whoever actually recorded the event, for what reasons it was recorded in the first place, whether whoever translated the records did so properly? And then you have to worry about the Historians themselves (the equivalent of worrying about the experimenter), are the historians providing all the data, are they incompetent, are they maliciously hiding something?

In science there is no way for any two observations to actually contradict each other, if there seems to be a contradiction then that has to do with the assumptions being made. In history there are a lot of cases where the observations contradict each other and only one is right (if we even get the right one!) so I feel much more comfortable with Science than History.

“consistent results for 200 years — and whose meaning was agreed on for all that time — is a very reliable bit of knowledge indeed” Yes. If scientists have agreed. The problem is if you found a historical record of some experiment that nobody remembered you would not be as certain of the results than if you performed the experiment. You would not just trust some ancient text (after all there could have been a paradigm shift in the meantime, or the original recorder was lying…).

“but they weren’t called angels, the text doesn’t say whether one of them (or all of them) was YHWH, and doesn’t even say what happened to them.” Actually one stayed with Abraham and two went to see Lot in Sodom. Then all the males in Sodom tried to rape them (wanted to “know them” is pretty obvious, especially when Lot offered his two daughters to them and they refused). The two people then blinded the Sodomites (using magic!) and then told Lot to leave. As Lot was leaving someone nuked Sodom.

I found it: Genesis 19, 1 (beginning): “The two angels came to Sodom in the evening…” The translation I have gives the note that: “The relation of the three visitors to the LORD or YWH (v.1) is difficult. All three angels (19.1) may represent the LORD (see 16.7 n.); thus the plurality becomes a single person in vv. 10, 13. On the other hand, v. 22 and 19.1 suggest the LORD is one of the three, the other two being attendants.” So it seems that it can go either way. I just find the idea of a plurality interesting.

“it’s hard to claim man’s soul is immortal” well, I have heard it claimed in many religious things. The idea of an immortal soul seems to be a part of Christianity at least (and Plato too…). So someone does make the claim (right or not? I dunno). “Anyhow, “immortal” means “undying”, not “indestructible”.” So, if God is immortal… he can destroy himself? Immortal isn’t indestructible! But then you get into the meaning of “eternal” etc.

I should probably sleep.

I think you mean confidence, not certainty. There’s no use in having degrees of certainty, nor gradations of uniqueness or death or pregnancy. Either you are or you aren’t. But the same is true for history — your confidence in a statement of history should be proportional to the strength of evidence for it.

Yes, that’s how history works as well.

It’s the same thing — writing history and interpreting history. When the war happened, people recorded some things and didn’t record others. Why? Because they felt some things were significant and others weren’t. That is interpretation. We have to find what happened in spite of their errors of interpretation. Nobody can record ALL events — if for no other reason than that we can’t SEE all the events. Your next paragraph explores that well:

This is all part of science as well. Your first sentence was entirely accurate. Another source of problems present in both science and history is that both start observing the event with assumptions of what’s important about the event. The shopkeeper starts by assuming that the damage to his shop is important, and he writes that in his journal; the general assumes that the damage to the opposing army is important and writes THAT in a communique. The later researcher gets both.

It’s a common fallacy that history is written by the winners. Any cursory look at a history text will prove that. Most of the time, the losers survive defeat, and their records do as well. Yes, the winning culture will build cultural myths; but that doesn’t eliminate the actual historical evidence.

And the science reporter, and the science teacher, and the science student, and the public at large, and the politicians, and the… Actually, science has all but one source of bias that history has: science can be experimentally reproduced, and history can’t. Science has the edge there. The problem comes when you try to determine whether a given result has actually been reproduced: you have to look at history.

Nobody cares what the direct results of the experiment are, even the scientist who does it. They care about whether the experiment denied the hypothesis, or the null hypothesis. We don’t even measure the things about experiments that we don’t think will affect that question (for example, would you care whether Archimedes set up a radiation detector near the crown while he was busy testing its density? Yet that’s important near the collision point in a supercollider!). Choosing what data to record is part of experimental design. Get it wrong and your experiment won’t be able to confirm or deny your hypothesis.

…or someone could have modified the text, or…

Right. But you can’t just trust a modern text either. In both cases you need more evidence — more historical evidence, specifically. And when you can’t trust the text, there are REASONS you can’t, and those reasons can themselves be investigated. Do you think the Catholic Church modified the text of the Bible to reflect its doctrines? Well, check that by collecting texts produced by the Coptic church, or the Dead Sea scrolls. And so on.

Radical doubt about history is itself a historical position — it’s NOT the absence of a historical position. And the evidence in many cases contradicts it. There are things in history that we know with high confidence; radical doubt is not a valid presupposition.

-Wm

(different topic:)

You’re at least part right (and I was wrong) — it’s clear that one of the three men become called “the LORD”, and the other two are then called angels. But that one is never called an angel; only the other two are so called. From what I can see, all three started out as “men”, then two became identified as angels after the one was ID’ed as “the LORD”. So it’s pretty remote to identify that as a manifestation of the trinity — it’s unlikely unless all three were addressed as “the LORD”.

It looks like the text is trying to say that two were revealed to be angels, and one was revealed to be God, NOT that there were three persons in God.

Note that the reference to 16:7 is actually a reference to a note. I don’t know what that note says; what version are you using? 16:7 itself refers to “the angel of the LORD”; some readers think that this is an appearance of God, but as far as the text goes, this is always singular.

And after the plurality becomes singular, the other two “men” are mentioned as “angels”, so it’s not that the plurality becomes singular (I misread that myself), but that the other two aren’t being mentioned until they figure into the story again — and even after they’re mentioned, the one who’s referred to as “the LORD” still goes on.

It is an odd doctrine, isn’t it. And I say that with respect, being one who actually believes it!

As I explain, “immortal” can mean many things. Not experiencing death (in which case man’s soul is objectively not immortal), not itself being killable (in which case most religions and folk traditions hold that it’s technically immortal). And I guess we can now add the category of not being destroyable — but that seems to me to go too far.

Right :-). And “outside of time”. (Does God live in his own timeline? Shrug.)

-Wm

Confidence is a better word.

“It’s the same thing — writing history and interpreting history”

No it’s not. Or rather, yes, but not in the same way. The person writing the sources that will be interpreted at a later date is kind of interpreting what he or she has seen/done/heard etc. Consider this: For years all scholars had access to on the subject of the Qing dynasty in China were the Chinese records. So naturally they worked with those and came to believe that the rulers (who were Manchu, not Han Chinese) had become sinicized (turned into Chinese, or absorbed etc). However once access to the Manchu records became available this is shown to not be the case. The Chinese sources never changed, they just found new ones. And I was referring to primary sources when I talked about writing history. And there certainly is a difference between primary sources (actual history, the evidence left behind, clues to what happened) and secondary sources (interpretation of primary sources to find out what happened etc).

“Another source of problems present in both science and history is that both start observing the event with assumptions of what’s important about the event” I am not certain about how this works for historians, but scientists start with gathering previous information and then forming a hypothesis from that information, then they try to prove that hypothesis wrong. That is an important part of an experiment. It would seem to me that historians first gather the facts then form an idea, or hypothesis, from there. In other words historians are stuck at the hypothesis stage, they cannot actually test that hypothesis, they can only hope for more data to appear to increase (or decrease) confidence in their hypothesis. Scientists can actually conduct experiments to figure out if the hypothesis is correct. That is a big difference.

The losers may survive defeat. And their records may survive. Or, they may not. We know that there may actually have been a Troy. We do not know what happened, if the Greeks destroyed it as claimed, or if something else entirely happened. And if the culture we are living in are the “winners” then we will very likely have interpretations that are skewed. The USSR failed because Communism was bad. What if the USSR failed because of the arms race? Or because of a reason separate from capitalism, like the huge industrial differences between the two countries (that existed FAR before the USSR went commie), and that the USSR could not ever close. But nope. It’s because the US was capitalist and could therefore outspend and out produce the USSR. Is it really? Maybe, but it was far too short a time ago to be truly confident.

“science has all but one source of bias that history has: science can be experimentally reproduced” And this gives Science an important edge when it comes to confidence. And Science does have at least one other advantage. The sources never change, and never degrade, and never encounter conflicting sources. This is because the rules of the universe do not change (or so it would seem… Dun dun duuunnnnn). The universe is like a gigantic primary source, and it is the only primary source when it comes to science. The universe is like the bible of science, so sure there will be differences of opinion on the interpretation sometimes, and uncertainty, but their isn’t a conflicting source! (Like the Bible and Quran giving God slightly different attributes would be a conflicting source…).

Sometimes people care about the direct result of the experiment (oh it goes boom…). And what I meant by that was if there was a record from 200 years ago that was relatively unknown that you just found, and it detailed the hypothesis and the results of the experiment. Then you would not just accept that old, unknown, experiment as being true. If you did the experiment yourself than you would know for sure.

“Radical doubt about history is itself a historical position — it’s NOT the absence of a historical position. And the evidence in many cases contradicts it. There are things in history that we know with high confidence; radical doubt is not a valid presupposition” Oh I didn’t mean that. I just have more confidence in science than history, but I certainly hold history in high regard, often even if it is not the correct history it can still teach us something.

And yes, I do think that the Christian church modified the bible… and voted on Christ’s divinity in the process. Thanks history! I’m just too lazy to check. Heh.

Back on that other Topic:

“But that one is never called an angel; only the other two are so called.”

Point. I think. But the two are also called men, then called angels, then called men again. Terms seem mutable. There are also points where it is uncertain which of the three are actually speaking… This is why people interpreting the bible should learn Hebrew. Gah.

“Note that the reference to 16:7 is actually a reference to a note. I don’t know what that note says; what version are you using?” Oops. Sorry about that, referencing a note… Grr. And as for the version… I think it is “New Revised Standard Version” Oxford University Press, 1991. The problem is that I can currently only find a few pages (it was printed out like paper for a binder), and I am basing which version it is off a bibliography of an old essay which I used it in.

“It is an odd doctrine, isn’t it. And I say that with respect, being one who actually believes it!” Odd isn’t bad. Odd is often good. And odd is also interesting!

“And I guess we can now add the category of not being destroyable — but that seems to me to go too far” So which one is God? And if being indestructible is going too far… than if God is immortal that immortality doesn’t make him indestructible. Which means he then could destroy himself? Though I suppose that doesn’t mean that there isn’t some other characteristic that would make him indestructible (sooo many negatives!).

Till next time, have a nice day (or week, month, year, decade, century, millenia, aeon, uh whatever comes after that…).

Sorry for the huge delay!

I’d love to discuss this… I erased a few blah-blah paragraphs — but it’s not really pertinent. However scientists work, historians typically make their best progress when they use the same basic methods.

That’s exactly what you just said scientists did.

You’re missing the fact that historians, like scientists, can also search for more data. Consider Schliemann’s discovery of Troy — he formulated a hypothesis (Troy existed in the place and time Homer described it), then a null hypothesis (Troy didn’t exist), then an experiment that would distinguish between them (go to the location, refine it by local custom, and DIG).

It’s true that the specific data you’re looking for might have been destroyed, but the corresponding problem in natural science is that your null hypothesis is insufficiently differentiated from your hypothesis, and your experiment therefore can’t possibly tell the two apart.

But there’s a more fundamental way in which you and I can’t be more certain about science than we are about history. Both subjects make authoritative claims about the world, and neither of us have within us the authority to dismiss or accept those claims as a whole, and few of us have the authority to dismiss or accept even a few of those claims. Is General Relativity a useful approximation? Is Global Warming anthropic in origin (and can it be held off by anthropic response)? Good questions, important questions — but not ones I can possibly answer. Does humanity bear Neanderthal DNA? Did Adam and Eve exist? Did Jesus rise from the dead? Was He worshipped as God during his lifetime — and did He reject that? Also good questions, and also not ones I can answer. In both cases I have to look to authoritative answers somehow — and whatever way I choose (that’s a different question), there’s no obvious reason why I should choose a different way for knowing the conclusions of science than I use for knowing the conclusions of history. Therefore, whatever epistemic difference might hypothetically lie within the people doing the research (which I deny anyhow), we as onlookers do not share it; we must accept or reject both based on the same rules.

And then there’s another twist. As I’ve said above, not only do the practitioners of science and history work in the same method, and not only do we in the general public accept or refuse their conclusions for the same reasons; but the fundamental difference between uncertain knowledge and certain knowledge is fundamentally historical in nature. Suppose that it’s important, for example, to know whether the fact being asserted is the result of a single experiment conducted by a single expert, or a consensus reached after hundreds of critical examinations, or the invention of a solitary quack: that question will be answered only by history, no matter whether the question you originally asked was scientific or historical in nature.

Is there any alternative? Is it reasonably possible to actually answer those questions on your own — to be your own authority? It doesn’t seem possible to me; even the modern greats, like Hawking, Dawkins, and so on don’t actually know their own entire field, much less all of science. When challenged to justify their beliefs, they point not to their own papers and experiments, but to the broad, settled consensus they know (_historically_ know!) is present.

-Wm

This has gone on so long I fear I might end up repeating myself. Whatever, here we go:

“That’s exactly what you just said scientists did.”

Well yes, at first, but historians don’t test their hypothesis, they can’t. Historians cannot go back in time and see if it all fits. Scientists can, sorta, in a manner of speaking.

“You’re missing the fact that historians, like scientists, can also search for more data. ”

Okay, yes, Troy was an archaeological discovery that gave more evidence. Definitely. Strong evidence, but it is not the same thing as testing the hypothesis that troy existed (which would basically mean going back in time and watching them build it). Then again, do we really need to test it now? Do we have a strong enough case? Probably. But is it the same Troy? Was it called Troy? We don’t actually know that.

Coming right down to it, you cannot test history as someone tests a scientific hypothesis. And that type of testing lends a credence to it.

And don’t get me wrong, sometimes that testing is not required. History is like a detective finding clues to a murder (and how it happened), then presenting the evidence to a court. Science (often) is like watching the murder unfold. But you don’t need to have actually seen the murder happen to be convinced the murderer is guilty. And sometimes the gathering of clues is more fun (I’m more likely to go into history than the sciences). But what provides the greater degree of confidence, seeing the murderer, or using evidence litter around the crime scene?

“But there’s a more fundamental way in which you and I can’t be more certain about science than we are about history…”

History and science are definitely similar in that regard. Oh yeah. Both do make authoritative claims (but which with more authority?), and neither of us can really accept or dismiss them in their entirety. Definitely true. “What? We’re mostly empty space? Pshh!” We on an individual level cannot really critique the theory of relativity. And the questions you posed are not ones that, for the most part, have been answered with either science or history. And neither communities actually are in full agreement on those subjects. Some answers the community may provide in the future, but something that individually is difficult to judge or make appear in our heads. Thank you Science and History communities!

So wait. Are you saying that both are as certain to you? Because for both cases we have to rely on authority to get our facts? I agree in so far as I cannot test scientific and historical theories myself (I don’t have access to all the primary sources or fancy equipment). But the subject matter and evaluation of knowledge within the sciences and history is definitely different, and I think that does make a difference.

“And then there’s another twist…”

Okay. I see that. But the thing is that most scientific experiments are reproducible. As is testing mathematical theorems etc. History is not reproducible, and that is an important difference.

With regards to Hawking, Dawkins, etc, like all scientists and even historians, they all have their respective communities as a support mechanism. This isn’t an attempt to refute what was said, but enhance it.

My main point is in the reproducibility of science and it’s testability as opposed to history. I think it makes a difference.

Now I gotta take the garbage out. Later!

Heh, those lucky astrophysicists :-). But you’re not just asking for too much here — you’re asking for WAY too much. History isn’t about knowing everything about the past in the same way we know about the present (that would only be solved by time travel); it’s actually more about knowing how the past is important to us now. Knowing the right question to ask is still the starting point, just as it is with science.

*Testing* the hypothesis means gathering information to confirm or deny the hypothesis. It doesn’t mean utterly *proving* it. Science never claims proofs of that sort; any scientist will tell you that such proofs are present only in math, not science.

Doing time travel to confirm history would be awesome indeed… But it wouldn’t replace the asking of intelligent questions. And anyhow, the profound question of history isn’t “what actually happened on this date”, but rather “how does this affect us now?” We do have to know what happened, but only to the extent that it redounds to this day — asking for more than that is not only a boring waste of time, but is impossible to discover, since anything that didn’t have an effect on the present can’t be detected from the present.

Hmm… There is one branch of history that does use time travel: cosmological natural history. It’s far from a settled art.

This is precisely where I claim you’re wrong. You can and DO test a historical hypothesis as you test a scientific one: you attempt to gather information which will distinguish between your hypothesis and its null hypothesis.

I’m glad you brought in the analogy; it’s helpful. I’m not sure it’s accurate; both eyewitness and material evidence are useful to establish historical facts, each in their own way. The eyewitness may not be the most useful, because human attention is often misleading. And then there’s the distinction between circumstantial and direct evidence… That’s the important thing. A lot of history is stuck with circumstantial (but corroborating) evidence, and if you think that’s the entire corpus of history, well, that would explain why you think it’s universally unreliable.

The problem is that once we get past the trivially obvious parts of science, we usually wind up with circumstantial evidence as well. How do we know that a neutron contains an electron? Well, you saw that neutron go into the collision chamber, and you saw an electron and a proton exit…

History is reproducible, though, as long as the researcher has kept his chain of custody clear.

The point of reproducing an experiment isn’t really to do the same thing and get the expected results. The point is to do a slightly different thing and try to distinguish a slightly different hypothesis-null hypothesis pair. Exact experiment recreations aren’t really that common, except when the result was truly incredible.

And those types of reproductions are possible in history. The historian reads some claim, looks up the citations, then in order to gain more information, comes up with some alternate sources to read. Perhaps the historian even thinks of a place to dig (but much more likely just reads the records of an excavation or manuscript find).

Who’s worse off — the atomic physicist, or the historian? Both may well be stuck with nothing but circumstantial evidence.

-Wm

Whoa, okay here we go!

History is about knowing what happened in the past. Then people can interpret that to their heart’s content. But establishing what happened and how things were in the past is what history is about. We cannot be certain of what actually happened because we were not there, and we cannot reproduce it. Am I asking too much? I am asking for a level of confidence that history cannot give me. Science gets me much closer to that then history does (if not actually there).

“Testing* the hypothesis means gathering information to confirm or deny the hypothesis. It doesn’t mean utterly *proving* it. Science never claims proofs of that sort; any scientist will tell you that such proofs are present only in math, not science.”

Yes, but, what confirms a hypothesis like “Troy existed” better than seeing it being built and called Troy and all that? Nothing. “Chemical X will cause the solution to bubble” when the solution bubbles (or doesn’t) that is like seeing the city of Troy. That provides direct evidence, that is something that science can do, but history cannot. Though true sometimes science uses indirect evidence, and often times history does not need direct evidence (seems to have gotten along fine so far eh?), but history cannot use direct evidence like that.

“This is precisely where I claim you’re wrong. You can and DO test a historical hypothesis as you test a scientific one: you attempt to gather information which will distinguish between your hypothesis and its null hypothesis.”

Excellent that we get this out here. Well, I should have noticed earlier (me stupid…), but this works to refocus things. “you attempt to gather information which will distinguish between your hypothesis and its null hypothesis.” Yes this is true. But the types of information that it is possible to gather are different (not completely, some are similar). History relies on the equivalent of circumstantial evidence, science does too, but it also relies on the equivalent of witnesses hooked up to an accurate truth device. (Damn I’m not sure this is an entirely sound analogy if taken too literally, oh well). The subject matter of the two is different and that causes there to be a slight difference in this regard as well.

“I’m glad you brought in the analogy; it’s helpful. I’m not sure it’s accurate; both eyewitness and material evidence are useful to establish historical facts”

Hmm, I didn’t mean eyewitness, more along the lines of the judge/jury/detective actually seeing the murder take place.

“The problem is that once we get past the trivially obvious parts of science, we usually wind up with circumstantial evidence as well. How do we know that a neutron contains an electron? Well, you saw that neutron go into the collision chamber, and you saw an electron and a proton exit…”

Yes. But you can do that experiment again and again. Does an electron and a neutron ever come out? No. History you can find one document that says one thing and one that says another, which one is right? The rules of the universe are objective (for our purposes anyway) and it’s evidence is rather clear. Not so much for history.

So even if science does rely on some circumstantial evidence (and yup it does) it seems to be better circumstantial evidence. Consider evidence in history, source one says Egyptians lost 100 people, source 2 says they lost 500. Who is right? Difficult to tell with just those sources.

“History is reproducible, though, as long as the researcher has kept his chain of custody clear.”

This is the logic used that is reproducible. Or the list of sources. The event that spawned those sources isn’t reproducible. You can’t build Troy again and say the ancient whoevers did it. You can split the atom and say “yup, thats how it works.”

One main point of being able to reproduce an experiment is to increase the confidence in the success of that experiment. See this lovely example: “Hey guys look, we did cold fusion!” “Great. Now show us.” “Could we get the award first?” “No.” (No they hadn’t pulled off cold fusion…). Reproducibility kinda helps the credibility along, as it does in history too. But in the end it comes down to the subject matter.

What is the subject matter of science? The ways that the universe works (in physics and chemistry anyway) or say the ways that life works (biology). What is the subject matter of history? What happened in the past.

The way the world works is timeless (for humanities purposes anyway), what has happened to humanity over time is most certainly not.

I want to be certain you agree with this (the last two bits, subject matter and timelessness) before continuing (or if you don’t agree then why not). If I went on I would be continuing to make stupid assumptions.

Sorry for the delay — I accidentally misplaced your post.

That nicely confirms “Troy exists”. It doesn’t address “Troy existed” at all. If you add some additional evidence that you’re actually witnessing something from the past of your own timeline — hard to imagine what that would look like — then you might have something very valuable for historical inquiry — it might be much easier than digging through libraries and/or excavations (although, on the other hand, it might be much more expensive and difficult, so it might actually be worse for most purposes).

After some thought, though, I think the answer I’ve been looking for all this time is simply this: you’re not actually distinguishing between science and history; rather, you’re distinguishing between direct knowledge and mediated knowledge. And that’s not a question of “science” or “history”; in fact, all direct knowledge is by nature historical knowledge, not scientific knowledge (it’s grounded in knowledge of your own personal history of experience).

Science is valuable because it doesn’t completely depend on direct knowledge. Science would make no progress if every scientist had to personally confirm every proposition on which he relied.

Your other examples are good, and I don’t mind talking about them, but I want to see if what I’m saying now makes sense.

-Wm

Hmm. Mediated knowledge and direct knowledge. interesting, I hope I understand what you mean by that. Though I think it sounds like a very good point.

Perhaps one could say that all in all history and science have different subject matter, and their very nature often means they generate different types of knowledge (that doesn’t mean completely separate all the time though).

“Science is valuable because it doesn’t completely depend on direct knowledge. Science would make no progress if every scientist had to personally confirm every proposition on which he relied.”

I totally agree with this statement… I, er, think.

I believe I understand what you mean, and I agree that it makes sense.

Very good point, both of them. Yes, both sciences (in the classical sense of “science”) produce different types of knowledge; and they can’t be separated, since they actually depend utterly on one another. You can’t learn anything about history if you don’t use natural science (otherwise, how could you analyse your historical evidence), while you can’t learn anything about natural science if you don’t use history (otherwise, how could you tell an established theory from some crank’s ravings?).

Sounds like we roughly agree.

Nonetheless, you’ve got one point in favor of your original conjecture: a few cultures developed some idea of history (this isn’t surprising — ancient cultures didn’t think in these terms), but only a couple (Islam, Christianity) developed the natural sciences, and those ones dominated. So science is very important, even if it depends utterly on history.

Note how I didn’t concede that until late in the game :-).

-Wm

“Sounds like we roughly agree.”

Yay!

“a few cultures developed some idea of history (this isn’t surprising — ancient cultures didn’t think in these terms), but only a couple (Islam, Christianity) developed the natural sciences, and those ones dominated. So science is very important, even if it depends utterly on history.”

Ah. And I didn’t actually come up with that. Damn. But it is a good point.

“Note how I didn’t concede that until late in the game”

I’d think that most people (myself included) probably wouldn’t either.

With this comment, I think it will make 50 on this page. Oh dear. Makes me feel sorry for someone who decides to read through the comic AND all the comments. And goodness knows how we got from immortality to Science and History! Nature of conversation I suppose.