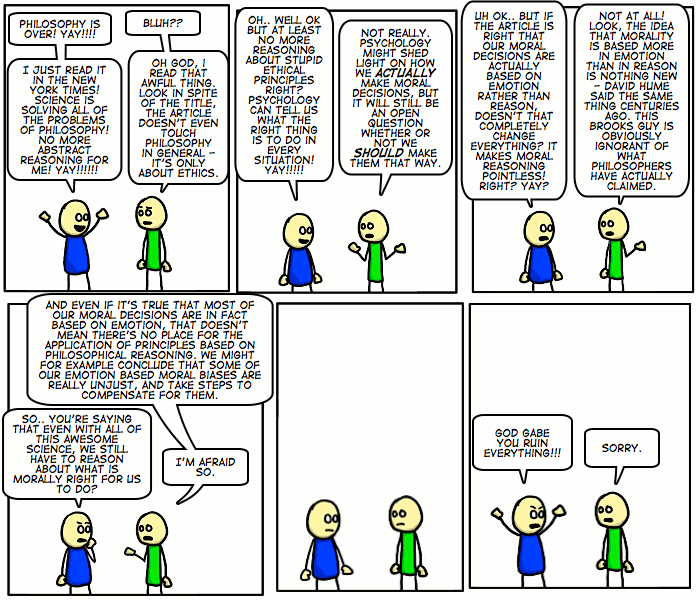

In case you haven’t seen it, the target of today’s comic/rant is a ridiculous piece in the New York Times by David Brooks titled (no joke) “The End of Philosophy”. The title is especially absurd because he doesn’t target philosophy in the article at all – just ethics, which of course (but perhaps Mr. Brooks doesn’t understand this) is a sub-field of philosophy, not philosophy itself.

The worst part is the nature of the argument against doing normative ethics. As near as I can tell, the argument is that since the sciences (psychology, socio-biology, etc) are giving us evidence that moral judgments are something we make automatically, based on emotion and intuition rather than reason, we needn’t concern ourself with speculations about moral principles or justifications or the like. Morality is all built into us already, so there’s nothing to figure out! Right?

Wrong. This argument is, of course, completely idiotic. It commits the naturalistic fallacy in a manner that I might expect from one of my intro-philosophy students, not from an Op-Ed Columnist in a major publication like the New York Times. The very obvious fact is that no amount of description of how we actually tend to make moral judgments is going to resolve the question whether those moral judgments are right or not. To answer that question, we’re going to have to engage in good old fashioned philosophical reasoning and argumentation about moral principles. It should be no surprise if reflective moral evaluation yields the conclusion that at least some of our natural tendancies and biases produce faulty snap moral judgments and we decide that they need to be compensated for in various ways. But this is something that Mr. Brooks’ position rules out in principle.

Anyway, here is a nice blog on the article by one Sabrina Jamil (who first brought my attention the article), and another one here by PZ Myers. They’re both worth looking at. And those of you readers who are involved in philosophy, or who care about it at all – please spread the word. These sorts of ridiculous misconceptions of philosophy are damaging to our discipline and need to be answered.

[…] NY Times which hardly lives up to its incendiary title; he is fittingly refuted in, of all places, this web comic by Chaospet. […]

Amen to that!

It’s not the first time we see such an obvious mistake by scientismers. (Yeah I just coined that. I couldn’t just call them scientists.)

[…] that the recent research in moral psychology spells the end of philosophical inquiry. Other bloggers have criticised it with the arguments we should expect from anyone who has at least stayed awake […]

It’s hard not to make fun of him, especially given the ending of that article (“Bob Herbert is off today.”), and how his Wikipedia page seems to imply that his own moral values have changed over the years.

[…] Brooks to task over his misreading of alleged scientific findings. Or, better put, Liberman finds a third-party cartoon that does the […]

[…] Chaospet gives David Brooks a well-deserved spanking on “The end of philosophy” […]

Seriously? How does this even pass for journalism? Nice job debunking that nonsense.

I’m don’t think Brooks is worthy even of that title – his grasp of the science (upon which he is making faulty inferences) doesn’t seem much better than his grasp of philosophy.

If you mean the “naturalistic fallacy” in the original sense of the phrase, I strongly disagree with the idea that it’s a fallacy. (Moore’s central argument to establish that it’s a fallacy–the Open Question silliness that could just as easily be deployed to show that water isn’t H20–is itself deeply fallacious.) If you just mean that there’s some silly is-ought slippage going on here, I totally agree. Brooks is….well…yeah….what you said.

[…] Chaospet: The very obvious fact is that no amount of description of how we actually tend to make moral judgments is going to resolve the question whether those moral judgments are right or not. To answer that question, we’re going to have to engage in good old fashioned philosophical reasoning and argumentation about moral principles. […]

Have students of philosophy forgotten to be charitable?

To read Brooks’s categorical mistake of taking ethics for ‘philosophy’ itself is not only uncharitable, but in my own opinion, the least persuasive way to question his claim.

If I read him correctly, he seems to say the following: the end of philosophy is here, because we have in fact discovered that there is no deliberation needed to make moral judgments, and subsequently, take moral actions. If this is the case, then he is at least quite consistent: why are we still championing philosophy if we are really unthinking brutes? And so the end of philosophy, which to say the least, is a form of disciplined reasoning.

It looks like Brooks’s claim can only be reasonably answered back by the tentativeness of scientific claims. As it is, we still do not know very much about moral judgments and how these judgments inevitably (if ever) lead to moral actions. I suppose we can debate on his definition of “intuition” but one man’s un-inspected intuition is just another’s quick (and perhaps disciplined) thinking after much practice. Dreyfus and Dreyfus’s work could not have been clearer on this point. But since in matters of moral judgment we cannot be said to have the same replicative kind and nature of practice as playing chess or judging the authenticity of art pieces, how can ‘intuition’ even apply?

And so I don’t think Brooks’s piece is ‘idiotic’ in nature; it is just trying to be sensational–a trick in the trade that gets you reading. On that part, I believe his judgment is right on.

Jef: We’re not disagreeing on what his argument is – read the comic and my blog again. What you describe is in fact precisely the fallacy I attribute to Brooks – the mistake of thinking that any account of how we actually make moral judgments in our daily lives answers the question of what the right moral judgments are.

chaospet: Thank you for your reply. If I may say this: In no place did Brooks actually make this following claim: how we actually make moral judgments answers the question of what the right moral judgments are. If I remember correctly, all he is claiming is: ‘this’ [fill in whatever he said cobbled from quasi-cognitive science] is how we make moral judgments. In no place did he said that the way we actually make judgments is the right way to make moral judgments.

Perhaps Brooks has gone to suggest that if this is how we make moral judgments, then there are prescriptive implications that follow from realizing that this is how we actually make moral judgments (i.e. thus we ought to do this and that). On this, I think that it is possible to claim that he has derived ought from ‘is’; but this is in fact quite different from claiming that he has derived the ‘right’ from some facts.

I agree that he is (at the very least) drawing prescriptive implications from the claim that we make moral judgments emotionally and automatically – namely that we shouldn’t bother with reasoning about moral principles the way philosophers do. And as I argued, this conclusion simply doesn’t follow.

But it also seems to me that he is pretty strongly endorsing the idea that this way of making moral judgments is actually right. For instance consider this bit:

” Think of what happens when you put a new food into your mouth. You don’t have to decide if it’s disgusting. You just know. You don’t have to decide if a landscape is beautiful. You just know. Moral judgments are like that.”

And if he doesn’t assume that the way we actually make moral judgments is right, and he wants to do away with reasoning about moral principles, then it seems like he is left with some sort of radical subjectivist position. Given what I know of Brooks, that doesn’t seem like the sort of position he would argue for – but I am open to being corrected about that.

chaospet: again thank you for your reply. This is very healthy and I appreciate your response. I like to think of this discussion and your moderation as something akin to approaching [non-disciplinary/non-departmental] philosophy; and by this, we rather need more claims, instead of that rare few, that ‘philosophy has ended’ for philosophy to flourish.

To be honest, I read him once in a while and so do not know if he is a card-carrying radical subjectivist or not. That said, I strongly suspect that a radical subjectivist wouldn’t even bother try making such objective claims to revoke principled moral judgments or moral laws; rather, Brooks’s claim seems to me arguing for a radicalized form of universal law concerning moral judgments and moral laws, not just because he tried to vanquish philosophy, but more so because he never considered other possibilities for moral judgments and actions, beyond the extreme poles of [hard-core] intuitionism and rationalism respectively. Insofar that this is concerned, his work reminded me of another piece of work–but not so easy to dismiss or vanquish at all–by B.F. Skinner, who more or less argued based on this kind of rhetoric.

By what you have quoted on what Brooks said, I suppose it is only possible to conclude as you have done if these words “it is right” subsequently follow from “you just know”. Because it is possible to know something without also knowing if it is right or wrong (1), and because it is possible to ‘know’ by the visceral, by the emotive, and even by “blink”(!) without committing also to the judgment that these various pathways of ‘knowing’ are morally right or wrong (2), I cannot conclude like how you have concluded unless what Brooks said also encapsulates both (1) and (2). Since how I perceived Brooks said to be exclusive of (1) and (2), I conclude otherwise: that what he said (your quote) does not endorse that this way of making moral judgments is actually right.

In all, I also suppose that to the extent of what Brooks has in fact claimed neither makes his claim true nor right. To the extent that it is not true, he has only attacked and discounted previous ways of making moral judgments, and perhaps even tried to make them false. But this does not make his own position true. And to the extent that he cannot be right, well, the jury is still out on his (very nascent) universal claims on moral judgments.

I’m not sure that I have much more to say to in defense of my way understand what Brooks is up to. It just seems pretty clear to me that he endorses the emotional/intuitive way we make moral judgments. He goes on at length about all of nice features of our evolved moral tendencies – how it promotes care for loyalty, respect, tradition, religion, etc. In doing so he seems to embrace our naturally given moral tendencies as the right ones.

But I suppose we can disagree on whether he is really committed to that claim, and still agree that he is committing what I take to be the more egregious error – concluding that there is no place for moral philosophy based on the fact (if it is indeed a fact) that we do typically make moral judgments in this intuitive/emotional way.

First let me say thanks for the new post!!!

After that my comment is basically this, is there any mention of a specific timeframe that Brooks is thinking about when he (seemingly) suggests there is no use for moral philosophy?

If he is saying to outright eliminate it, then yes I can totally agree with the rest of you.

Ethics are constantly changing with new technologies before we were able to travel vast distances we didn’t need to worry about the moral issues of interracial couplings. Before the internet we had no reason to morally think about the ethical decisions within file sharing (much love and good luck to TPB). New technologies will evolve that require new moralistic thought and philosophy.

If however he were to prune his idea down to “when in the midst of a moral decision there is little use for philosophy” I can understand and agree with that as a single point.. I do realize that that was not the tone of his article but I believe it to be an idea worth developing in its own right. You are the person you are with all of your prejudice bias etc.. If you are self aware enough to internally analyze you can use moral philosophy before or after to change the underlying psychology you may have and thus change your decisions for the better. In the heat of a real decision on the other hand debating the morality I find to be wasteful to the point of damaging because of the reality of how you make your decision is not relevant to whatever philosophical spin you can and will put on it.

Also WOOT! To see all the lively debate again! keep up the great work chaospet and commenters!

Brooks doesn’t do a great job here but his point is basically right. If morality is a quirk of evolution and out intuitions about morality are not based on any objective understanding or criteria, then there is no point reasoning about it. We should just accept that if you think abortion is wrong, then that’s how you feel and that if I don’t then that’s how I feel. No argument is going to settle the matter.

The history of moral philosophy has largely consisted of people examining their intuitions and trying to come up with a coherent framework. There’s no reason our intuitions should be coherent. It’s perfectly coherent for me to feel negatively about the proposition of killing people but to feel positively about the proposition of killing people in battle. Just as red can be my favourite colour in general but I might prefer blue cars.

[…] It’s always best to express oneself with a cartoon: The End of Philosophy. […]

@chaos872: That’s a good distinction to make. I take him to be arguing for the stronger claim – he seems pretty clearly to be attacking the practice of trying to find moral principles and apply them.

But even if we read him as advocating the weaker claim you suggest, I’m not sure it follows. Even if he’s right that we generally don’t make moral decisions in the heat of the moment that way, it doesn’t mean we are completely incapable of doing so, and it might be worth the effort to pause and ask ourselves if our present intuitions or feelings fit with the principles we would accept in our reflective moments. I would think that sometimes that can make a positive difference.

@Finnsense: I would disagree with you about two points. One is an empirical point – I think arguments DO sometimes change people’s intuitions about particular moral issues. I’ve had it happen to me (for example on animal rights), and I’ve witnessed happen a number of times as an ethics instructor. It usually doesn’t happen easily, but it does happen.

And second, I don’t think that moral philosophy is primarily about finding a framework or set of principles that accommodate all of our intuitions. One of the things moral philosophers have done since the beginning is argue that some of our intuitions are mistaken – Mill and Bentham for instance strongly argued against slavery on Utilitarian grounds, at a time when the vast majority intuitively found slavery to be quite acceptable.

In other words moral philosophy is not primarily a descriptive enterprise – it’s not trying to find a way to characterize the manner in which we actually make moral judgments. If that’s all it was, then yes the psychological data Brooks points to would threaten it. Moral philosophy is primarily prescriptive, trying to figure out which of our intuitive judgments are right and which we ought to reject. And while empirical data from psychology can be relevant to that project (particularly in enlightening us about which tendencies we actually have in making moral judgments), it can’t replace it.

“but his point is basically right. If morality is a quirk of evolution and our intuitions about morality are not based on any objective understanding or criteria, then there is no point reasoning about it.”

Non sequitur. Our intuitions about morality are not the only thing that guides our behavior. We occasionally allow careful reasoning and other people’s advice to overcome biases — sometimes rightly, sometimes wrongly.

“We should just accept that if you think abortion is wrong, then that’s how you feel and that if I don’t then that’s how I feel. No argument is going to settle the matter.”

But the matter isn’t whether I think abortion is wrong or you think it’s wrong. The matter (in this example) is whether abortion should permitted and for what purposes. It’s not even possible to settle that by simply agreeing that we all have different opinions; both sides want to _act_ on those opinions.

@chaopset: I agree that arguments do change peope’s opinions but I would disagree that it is the quality of the argument that invokes the change. I would also argue that where change occurs it is usually due to the acceptance of certain empirical facts (as well as pressure). Is seems to me more the business of empirical psychology than philosophy, to work out why our opinions change.

I agree that we don’t think ethics is a descriptive exercise but strange then, that most arguments against ethical theories are based on the fact they conflict with our intuitions. Anyone who tries to justify their “starting point” ends up failing. That’s true for Mill, it’s true for Kant.

@Wm Tanksley

What we do in practice and what is worth doing are two different things.

As to your second point, the question for moral philosophy really is whether or not abortion is wrong. If it is, don’t do it and feel justified prohibiting others from doing it. If it isn’t, feel free to do it and don’t prohibit others from doing it.

That question is unanswerable so the practical issue becomes “Give that we don’t know one way or the other, what should we do?”. That depends what society we want to live in but it’s a practical not an ethical question.

People in general are often moved by poor arguments, not just in ethics. It doesn’t follow that there is no point to arguing and reasoning and trying to figure out what is actually the case. The question of why our opinions in fact change is indeed a question for psychology. The question of what the right opinions are is not, not in ethics and not in any other discipline.

There’s no doubt that moral philosophy involves appeal to intuitions, but that’s not inconsistent with what I said. It also involves arguments for why certain intuitions are the ones we ought to appeal to and others are not. So again, it’s not just a matter of trying to systematically capture all of our intuitions – it never has been. Brooks’ “insight” does not undermine the practice of moral philosophy – if anything it highlights the importance of doing good moral philosophy, to figure out which of the intuitions and emotional tendencies given to us by evolution track morality and which don’t.

You seem to be assuming a strong subjectivism about morality. That could be the case, but it needs to be argued for on different grounds – it simply does not follow from any descriptive facts about our psychology or evolutionary history.

“You seem to be assuming a strong subjectivism about morality. That could be the case, but it needs to be argued for on different grounds – it simply does not follow from any descriptive facts about our psychology or evolutionary history.”

I’m afraid this is a mistake. To assume morality exists (i.e. has content) you need evidence – just as you need evidence God exists. The evidence for the existence of God becomes much weaker if you accept the fact of evolution (because it explains the appearance of design). Likewise, the insights of psychology and biology do not prove a priori, that morality does not exist (and by that I mean that there is no content to the phrase “X is wrong” etc) but they do give an exceptionally strong presumption against it.

Just as it is not absurd to believe in God, it is not absurd to believe in morality. However, the empirical evidence suggests that both do not exist. It is up to philosophers to prove they do if they want to continue examinig the issue in that way.

The evidence that Brooks points to does not give any reason to presume that there is no objective morality. Let’s consider a parallel case. Suppose it were pointed that in fact our evolutionary history has endowed us with a mess of logical intuitions. What inferences we think hold in particular cases is typically a snap intuitive judgment, and our intuitions about inferences are often inconsistent and messy (and in fact there is plenty of evidence that this is the case). Should we conclude then that logic doesn’t exist? That it’s all subjective? That there is no content to logical statements – to statements about which inferences we ought to make and which ones we shouldn’t make? That there’s no point to doing logic? It seems to pretty clear that none of these claims is at all supported by empirical evidence about how we actually draw inferences in typical cases. Similarly, no claim about the objectivity (or subjectivity) or morality is at all supported by empirical evidence about how we actually draw moral conclusions in typical cases.

The point again is this: merely describing our psychological tendencies in how we actually make judgments in any domain, be it ethics, logic, mathematics, etc, does not tell us anything about whether any of these judgments are right or not. They are distinct questions.

Now yes of course, someone who wishes to defend the objectivity of morality needs arguments. So does someone who wants to claim that morality is subjective. And similarly for anyone wants to claim that logic is (or isn’t) objective. My point is only that none of these claims follow from the kinds of descriptive facts Brooks has highlighted.

That question is unanswerable so the practical issue becomes “Give that we don’t know one way or the other, what should we do?”. That depends what society we want to live in but it’s a practical not an ethical question.

“What should we do” is both ethical and practical. “Should” is ethical, “do” is practical. The way we answer that question is to decide. Not deciding isn’t a choice; doing nothing is making a decision.

Given that we don’t know, we could take several actions — we could be extremely cautious and ban everything; we could be extremely free and allow anything; we could establish an arbitrary, politically tenable compromise; or we could attempt to define terms and try to find out as much as we can know, and find a sensible action.

However, the empirical evidence suggests that both do not exist. It is up to philosophers to prove they do if they want to continue examinig the issue in that way.

I think chaospet has done an excellent job of explaining why ethics is a real discipline, a genuine part of philosophy. The question isn’t whether ethics is “real” in some empirical sense, but rather whether we should be thinking about ethics, whether it’s a valid field of study. (Hmm, it begs the question to ask whether we *should* be thinking about ethics — that’s an ethical question, so if you even try to answer it, you’ve assumed a positive answer.)

@chaopset

Logic is not the same as morality. We accept the validity of logical propositions because we have no choice. They describe the structure of our experience and cognition. No-one from any culture would deny the law of non-contradiction. Morality just isn’t like this.

I drew the parallel between theism and morality precisely because it is not of this character. According to your reasoning, in the absence of evidence of the existence of something there is no presumption either way. So aliens may exist or not but we cannot presume they do not, because we have no evidence. This is wrong. In order to assume that moral facts exist the burden of proof lies with person making the assumption. I am simply saying that I do not think morality as it is generally conceived exists due to lack of evidence. If your response is to say that lots of people have moral intuitions, my reply is to say yes, but we have an excellent explanation for why this is (not that we need it).

@Wm Tanksley

“Should” is not always ethical and it is not in the sense in which I use it. If I say “Jimmy wants some candy but doesn’t have enough money, what should he do” I am not asking for an ethics based response. I’m not saying we do not have to have a policy on abortion. I am saying that the considerations involved in formulating that policy cannot, coherently, be ethical. In practice we are balancing the ethical tastes of different people – but that’s not ethics. It’s like balancing the fact that some people prefer apples and some oranges.

As to your second point, my argument is that the questions raised by philosophical ethics are now best answered by science. We know to a high degree of certainty that our moral intuitions are an evolutionary development that allow us to live together – but that ultimately they are tastes – arbitrary and without foundation. Thus, we cannot reason about them because our premises are always questionable.

If you want me to accept that yes, all the evidence suggests our moral intuitions are explicable without foundation, but that there still is a foundation, you need to argue for it. Trends in metaethics suggest you would have trouble though. Forms on non-cognitivism seem to be winning the day there and that makes sense from an evolutionary standpoint.

Again, in this light the questions of ethics “what should I do”, “how should I live” are best restated in unambiguously non-ethical terms. “Given my desires and moral intuitions and the desires and moral intuitions of others, what action would best meet my ends” – might be a useful formulation – or something like it.

Finn: That’s just the point – formal logic does NOT capture the way we actually experience the world. The formal fallacies have to be described precisely because they are so intuitively appealing.

Nobody would deny the law of non-contradiction? Wrong. You should talk to Ben, or look back through some of my old comics on dialetheism. It’s not a common position, but folks like Graham Priest do advance notable arguments against even the law of non-contradiction, and they do have to be answered.

Your argument is taking quite a different turn. Your initial claim was NOT merely “I do not think morality as it is generally conceived exists due to lack of evidence”, it was that the science Brooks pointed to provides evidence that doing morality is pointless. Now you’re running the line that the burden of proof lies on the person who claims existence, which I generally agree with – when we’re talking about existence claims. But I am not making any strong ontological claims regarding ethics – I don’t think that “goodness” is a distinct natural property in the world or exists in a Platonic realm (nor would I say that about “entailment”). I’m not arguing for that kind of realism – I agree, there would be a considerable burden of proof on anyone who made such a claim.

All I’m saying is that ethical claims of the form “X is wrong” may be true or false, just as claims of the form “Q follows from P” may be true or false. I think the prima facie evidence in favor of objectivity of both sorts of claims is enough to level the playing field. Further arguments have to be made to support the position in either case – as I acknowledged – but merely pointing to the fact that evolution explains our intuitions about such things, for either logic or ethics, provides no evidence one way or the other.

*edit*

I just found this piece over at the Discovery Institute’s site, and thought I would share because it fits well with our discussion here. The author argues – in much the same way that you do – that it follows from our moral intuitions having an evolutionary history that there is no objective morality. And then he runs the exact same argument from evolution against objective reason. I think both arguments are making the same very obvious mistake – that no normative claims about reason or ethics follow from such descriptive claims. But the article illustrates what I have been saying – that the sort of argument that you’re making, if it WERE right, would have broad implications well beyond the field of ethics.

Finn, another point… I was just reading the results of a large group of twin studies. In a twin study, the twins were separated at birth, grew up apart, and later their upbringing and outcomes are studied. My understanding is that some 90% of their outcomes are correlated with the fact that they’re twins, NOT any part of their upbringing; in other words, it seems that genetics is the strongest determinative factor in our life outcomes.

This is how science looks at it.

Now what do we conclude? Should we stop studying philosophy of ethics because it has only at most 10% effect on people’s actions? It seems to me that in order to answer that question we must go beyond science and into ethics. And once we’re there to answer how to deal with the science, why don’t we stay and think about how to act? Perhaps that 10% will be worth changing.

Given my desires and moral intuitions and the desires and moral intuitions of others, what action would best meet my ends

Ah, the field of praxeology! I love that stuff. Not the same as ethics, though; ethics is about choosing which desires and moral intuitions to develop in oneself and incentivize in others.

Hmm, here’s an argument. If science had shown that 100% of our outcomes were the result of genetics, would the study of ethics be improper? It’s clear that actual ethical discoveries would be irrelevant, since people before and after the discovery would have the same outcomes; but the study itself would still seem as valid as anything else, since clearly some people are genetically predisposed to perform those studies and publish those results.

Of course, the studies fail to show this; they show about 90% genetic correlation, thus giving 10% slack for ethical discoveries to influence people. Furthermore, this is what I would expect if ethics are objective: there’s only so much you can change using ethical teaching, because the wisdom you’re teaching is already in some sense encoded in most people in some way (and now we know how — genetics).

Off topic, but since it’s Easter, I thought I’d say: “chaospet is risen!”

Although in keeping with the traditions, I have to complain that we didn’t get an Easter cartoon. (No, the tradition isn’t the cartoon; it’s me complaining constantly about non-problems.)

Wm: Haha, nice. If I had thought of it, I might have postponed the triumphant return of chaospet until today. Then again if I’d done that I wouldn’t have been able to do a timely comic on the Brooks article, which has generated a lot more attention and lively discussion than I’ve had here in a while. Ah well. 🙂

As someone who knows very little about the field(s) of philosophy as a whole, I can claim without any evidence that Brooks focused on ethics because it is probably all that he is really aware of. outsiders, like myself, tend to only see the “fun” stuff. Which ethics is.

So ya. That.

Oh ya, also, ethics seems more relevant when you aren’t aware enough of other subjects to see their relevance. I also believe that *because* everyone makes their own moral judgements naturally, they feel less alienated from an intellectual discussion on them. they’ve done it, it can’t be so hard right? I mean, ask someone what they think is right or wrong and they already have an answer, no further thought needs to be made, you just have to speak your mind.

Typical beginner mistake I would expect, one that I found, and still do from time to time, myself making often. That the majority of my moral judgements remain the same is dumb luck. Or I’m not as capable of seeing past my emotive reactions as I though.

Anyway, way too much ranting. That is my perspective as someone who really doesn’t understand philosophy as a whole. Untrained, undisciplined, unabashed… mostly.

Abeo: I don’t doubt that’s why he focused on Ethics, and as some others have pointed out, there’s a good chance the provocative title was concocted by an editor rather than Brooks himself. But the title is a smaller complaint anyway – my main issue is with the arguments he makes in the article.

Glad to see philosophy’s back (in comic form!)

Catchy title, but I’m in agreement with you that the notion that philosophy has ended based on such empirical data is ridiculous.

The beautiful truth is that there is absolutely nothing to give up That panic is just psychological.

I cannot tell you of the utter joy of being free of those sinister black shadows….

To one who has faith, no explanation is necessary. To one without faith, no explanation is possible.

An explanation of cause is not a justification by reason.

[…] Chaospet gives David Brooks a well-deserved spanking on “The end of philosophy” […]

Very nice!